Don’t grumble against one another, brothers and sisters, or you will be judged. The Judge is standing at the door!

James 5:7

Many of us have become experts in the Art of the Whine.

We complain about our politicians. We complain about the weather. We complain about how the manager went to the bullpen too soon (The starter’s pitch count was fine!).

My mom, drawing on our family’s Dutch heritage, calls this ceaseless belly-aching crimineering. It’s the ongoing murmur that signals our perpetual dissatisfaction with life.

Google around a little while and you’ll find that several websites have taken to archiving the society’s complaints (Many are NSFW, hence no links). There are angry letters about being seated by the airplane lavatory. There’s fury at opening a de-chocolated Snickers bar. You’ll see chagrin at being inadvertently billed $10,000 for a month of cable TV service, stuff like that.

A couple of these are worth sharing:

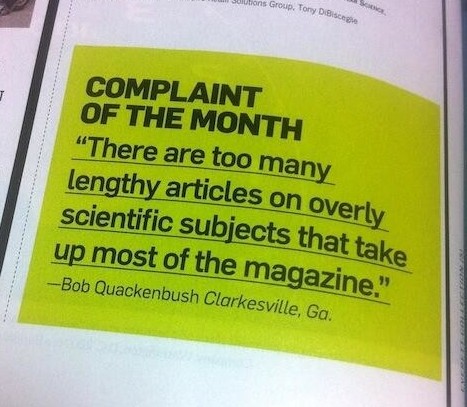

This one was found in the feedback section of a national magazine:

The name of that magazine is… Popular Science.

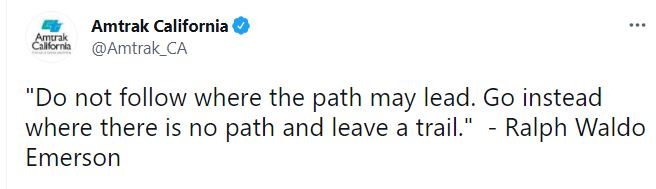

Other protests make more sense. A couple of years ago, Amtrak California tweeted this quote from Ralph Waldo Emerson…

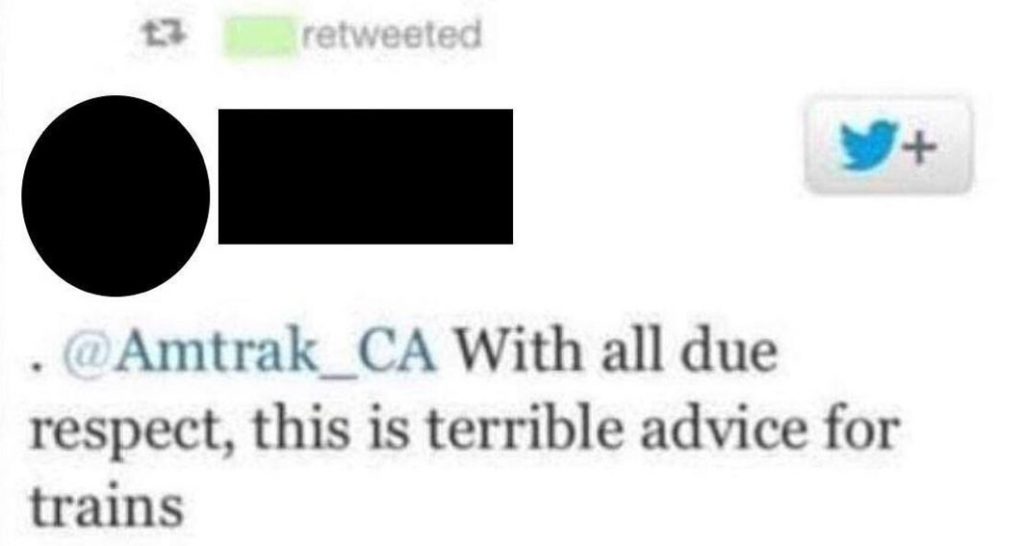

… which prompted this response from a thoughtful reader:

And yeah, if you think about it?

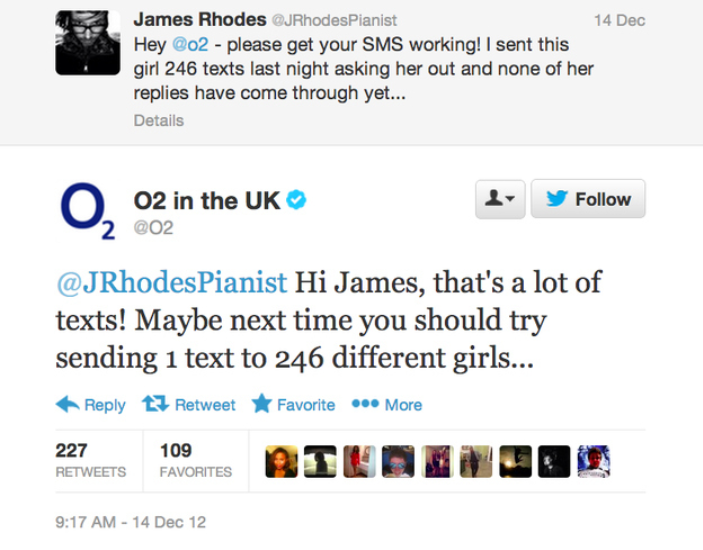

Occasionally, you’ll see a customer service account clap back pretty good when they realize the complaint is silly or irrational. Check out this interaction between Twitter user James Rhodes and the British wireless provider O2:

That. Is. Spicy.

Joshua Rothman begins his article about grumbling for the New Yorker Magazine this way:

Everybody grumbles—it’s a basic human behavior. Still, it sometimes seems as though everybody’s doing it more. Last week, I spent the day keeping track of my social interactions, asking myself what percentage included grumbling. The answer was nearly a hundred per cent.

So why is grumbling so common? After all, as football coach Lou Holtz once said, “You shouldn’t complain about all your problems. Eighty percent of people don’t care; the other twenty percent will think you deserve them!” Yet crimineer we do.

Psychologists have pointed to a couple of different reasons for our tendency to whine:

One, they say, there is something about sharing our frustrations with other people that sociologically bonds us to them. When we are honest about the things that concern us, we just feel more connected. In fact, Jane Wagner has suggested that humanity might have actually developed language “because of our deep inner need to complain.”

Other researchers note that folks have developed a tendency to talk more about the things that bother us than those that please us because we believe that other people can sometimes figure out solutions. It’s an instinct toward group gameplanning.

But whatever our natural inclinations, recent research suggests that all of this complaining and grumbling might actually be killing us.

This isn’t just preacher’s rhetoric. A number of studies have shown that frequent complaining spins up into serious health issues.

The more people complain, lab tests show, the more of a hormone called cortisol they produce. This becomes a snowball – the more cortisol is released, the more people tend to complain. Increased cortisol, in turn, corresponds with lower immune functions, lower bone density, increased weight gain, blood pressure, cholesterol, heart disease, and stroke. You can, in a very real sense, complain yourself to death.

Now, none of that may phase you. After all, you still eat bacon and drink Monster, right? So why should we try to draw down the crimineering?

In a significant way, it’s because the Bible teaches that grumbling also increases the threat of spiritual disease.

In chapter 5 of his book, James – the half-brother of Jesus and a man with a bent toward bluntness – describes a specific kind of complaining that happens within the church.

James knows what my uncle used to say about congregational life: Church is a group of porcupines huddling on a winter night; they gather for warmth, but in doing so they often end up poking each other.

In verse 7, he is calling out this intra-church tendency toward bickering and consternation. People in Row Nine brumming about people in Row Twelve. James thinks it needs to stop.

Now it’s important to note here what James isn’t saying. He isn’t suggesting that human beings never have reasons to be upset, nor is he implying that people shouldn’t vent their frustrations. Scripture makes it clear in lots of places that God does listen to complaints and that he responds to them in mercy.

Exodus 3, for instance, says that God hears the cries of the enslaved Israelites and that, in compassion, he activates a plan of deliverance from slavery. And the entire book of Habakkuk is a back and forth in which a prophet of God complains about the suffering his people feel and the answers that God provides.

James isn’t saying that injustice isn’t real. He wouldn’t say that within the church, we should always act as if everything is hunky-dory. (That is, if “hunky-dory” is still a thing. Maybe it left town with swell and groovy? Send me an AOL instant message if you know.)

What James is zeroing in on here is the indirect, low-frequency muttering that can settle into Christian communities.

Some translations use the verb “sigh” here. You know that condescending church-goer’s sigh?

Well, yeah, church is fine, but you know, Pastor George (sigh), he’s just never going to get it…

I like the music on Sundays, but (sigh) the elders never really do anything…

Our ministry to the homeless is on the right track, (sigh) no thanks to Belinda…

So why do we have so much grumbling in the church? What’s behind it?

Well, one thing we know about complaining is that it has a lot to do with a perceived loss of power.

Why do people write complaint letters to huge companies? Why do they send those tweets? Because they have nothing else they can do. It’s them versus Delta Airlines, and Delta has way more power than they do. It’s them versus Verizon. It’s them versus Pepsi, whatever. There are real inequities.

But what often happens in church is that we complain and grumble about power deficits that are more imagined than real. When we dedicate all kinds of energy to complaining, we are often giving others power over us that they cannot rightfully claim.

Grumbling about other church members implies that God can’t keep this church on the rails, that God’s not going to see this through…because Joanne Johnson is messing it all up!

Seriously? Is your God that small?

Trust me, Joanne Johnson is no Thanos. She isn’t that powerful. She can’t ruin everything.

The gates of hell cannot prevail against the church, and neither can Bob from Property and Grounds.

Also of significance in this text: James links the command to stop complaining to the nearness of Judge Jesus. What does it mean that “the Judge is standing at the door?”

Does it mean that Jesus is about to return, so there’s no point in complaining? Does it mean that grumbling is sinful, and Jesus will hold you accountable for your grumbling? Does it mean that we shouldn’t judge each other, when the only True Judge is so close at hand?

Or might it mean all of the above? Could it imply that Jesus is right here with us, finishing his work, and that we need to trust him through all of our frustrations?

Maybe what James means is that right now, nothing could be more important than accepting and loving one another in Jesus because Jesus is so madly in love with us. He’s hanging around, right at the threshold. He’s opening a door to an amazing future . He’s here, knocking, waiting to live in powerful ways in our relationships in order to create life and hope.

Anti-apartheid activist Alan Paton once said “I have always found that actively loving saves one from a morbid preoccupation with the shortcomings of society.” In other words, we can see the world as riddled reasons to complain, or we can approach life as an opportunity to live with compassion.

Maybe what’s most important to Jesus is that we remember all that he could have complained about (you don’t think we’ve given him reasons to be frustrated?) … but he chose to speak love and life anyway.

And that maybe, we speak – and decide not to speak – in ways more like him.