So God created mankind in his own image,

in the image of God he created them;

male and female he created them.

Genesis 1:27

One of my responsibilities as the leader of a church staff is to select and facilitate our weekly staff devotions. Over the decade that I’ve served at First Reformed Church, our hourlong studies have explored books of the Bible, discussed theological themes, and considered Christian living practices.

This autumn, I decided to try something new. Rather than analyze the latest work by Tod Bolsinger or Brene Brown, we’ve gone back in time. To 1984.

Written (somewhat confusingly) in 1949, 1984 is the dystopian vision of the British journalist George Orwell. From the wreckage of post-WWII Europe, Orwell described a forthcoming authoritarian world marked by suspicion, surveillance, and perpetual war.

In Airstrip One (the territory formerly known as Great Britain) Orwell’s protagonist Winston Smith negotiates a society dominated by the caprice of the Inner Party. Always apprehensive – and never entirely sure about what’s real and what’s contrived – Winston yearns for a life of truth, intimacy, and joy.

While most commentators believe that 1984 aims its critique toward Nazi and Soviet totalitarianism, many of Orwell’s observations have clear resonance with life in 2020. Terms like Big Brother, Memory Hole, and Doublethink – brainchildren of the author’s mind – have crossed over into common use. And given the historical editing, racial animus, and red/blue demonization occurring in our own times, our staff regularly notes the relevance of 1984 for today.

Among the ongoing concerns of the book is the question of personhood. What value does an individual have in a collective society?

For the ruling elites of Airstrip One, people have worth so long as they can preserve and advance the power of the Party.

The nation’s privileged men and women, plied with gin and propaganda, drone on in grey subservience. Cogs in a machine, they are born, indoctrinated, harvested unto menial tasks, reprimanded, and ultimately discarded. The treasonous few who dare to write, sing, or claim private property are condemned as “unpersons” by the powers. So much as a furtive glance (“Facecrime”) is punishable by death.

The members of Airstrip One’s lower class, the proles, fare no better. The contempt of the Party, the proles live in a perpetual murk, always deceived, forever mollified with porn and sloganeering. Orwell writes:

So long as they continued to work and breed, their other activities were without importance. Left to themselves, like cattle turned loose upon the plains of Argentina, they had reverted to a style of life that appeared to be natural to them, a sort of ancestral pattern. They were born, they grew up in the gutters, they went to work at twelve, they passed through a brief blossoming-period of beauty and sexual desire, they married at twenty, they were middle-aged at thirty, they died, for the most part, at sixty.

Top to bottom, the social order Orwell imagines thinks human beings debased and disposable. They are not marvelous. They are not discrete. They are not beautiful.

They are, at best, useful.

This reckoning of human beings – no doubt shaped by the horrors of mid-century Europe – is at great odds with the Biblical perspective on personhood. The Bible’s Page One Declaration is that men and women are created, male and female, in God’s own image (Genesis 1:27).

While theologians have sometimes wondered about what, exactly, “image-bearing” means (Is it a kind of title? A capacity? A responsibility? A conferred attribute?), they have long understood that what the author of Genesis is claiming is of incalculable political and religious significance.

The Hebrew word for image, tselem, is not an uncommon noun. In most cases, it means “idol” or “statue.” It was also applied to certain cultural elites; kings and monarchs were thought to be the image-bearers of their local or national gods.

What is stunning about Genesis’ use of the word is that it is applied to all persons. Rulers and servants alike bear the image of God. Natives and immigrants. Men and women. Party members and proles. They all represent their creator God. They have intrinsic value.

It’s little wonder why the Old Testament’s legal codes are so strict about the creation of material figures. Thou shalt not make any graven images. Why? They are unnecessary and profane, because you, yourself, bear the image of God!

Similarly, when challenged about tax policy, Jesus asked whose image marked the denarius. When the crowds responded that it was Caesar’s tselem on the coin, Jesus said: Good. Now render to Caesar what is Caesar’s… and give to God that which is stamped with God’s image.

People can’t be bought, Jesus says.

Genesis 1:27 takes on an even richer meaning when we consider the possibility that the text took final form during the Babylonian captivity of the Jews in the 6th Century BCE.

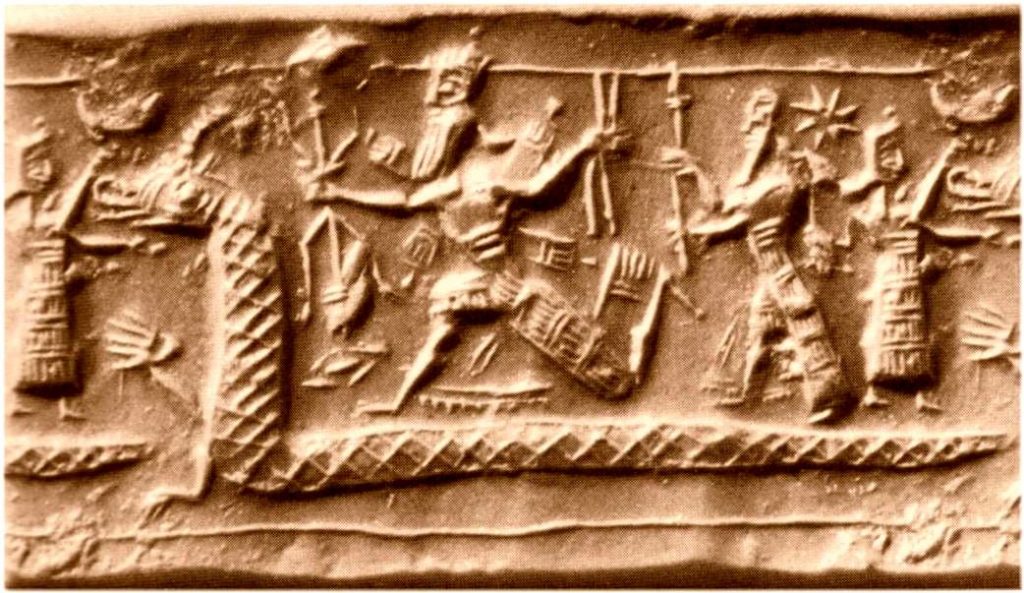

Though the matter remains open, many scholars have wondered whether the Genesis 1 narrative, which bears striking similarities to a Babylonian creation story called the Enuma Elish, presented a direct critique to their captors’ view of humankind.

According to the Enuma Elish, the Babylonian arch-deity Marduk heard the pleas of his fellow gods and created human beings to do the work that the gods had tired of doing. Tablet Six (of seven, coincidentally?) describes the making of man:

When Marduk heard the words of the gods,

His heart prompted him to fashion artful works.

Opening his mouth, he addressed Ea

To impart the plan he had conceived in his heart:

“I will take blood and fashion bone.

I will establish a savage, ‘man’ shall be his name.

truly, savage-man I will create.

He shall be charged with the service of the gods

That they might be at ease!

The moral of the story would have been clear to the ruling partisans of Babylon: We are like Marduk; we have taken these savages captive to serve us so that we might live at ease.

How brash and beautiful, then, for the exiled Jews to declare their own creation story in that time and place. With just enough similarities to the Enuma Elish to draw the Babylonians in, Genesis 1:1-26 would have primed the social overlords for the remarkable reversal of verse 27: We are menial slaves; though we are exiled and oppressed, we too bear the image of God!

The claim that all persons bear God’s image claps back at an impulse toward objectification that spans the arc of history. It lived in the first millennium BCE, it manifested in the 1940’s, and it plainly operates today.

By dint of an overemphasis on the collective over the individual (Scripture celebrates both!), as an implication of mechanical Darwinism, or perhaps as a result of the scathing political moment in which we live, we have devalued human life and disdained the audacious claim of the Bible: We all matter. We all have worth. We are not human doings, we are human beings.

As the US election approaches (and with it, the pressure to atomize one another along party lines), it’s my hope that my conservative Christian friends and my progressive Christian friends can find common ground here: We all bear the image of God.

Americans and non-Americans alike bear the image of God.

The born and the unborn alike bear the image of God.

Those with pre-existing conditions, as much as the vigorous and healthy, bear the image of God.

Those who share our moral vision, as well as those who do not agree, bear the image of God.

None of this, in the Christian worldview, is negotiable.

The more that we stratify our brothers and sisters according to their ideas, abilities, or ancestries, the closer we edge to an Orwellian disaster.

As those who share a spiritual heritage in the stunning claims of Genesis 1:27, let’s do better. Let’s resist the Marduks among us, choosing instead to honor each member of the human family with the dignity that comes from bearing the image of the Creator God.