Jesus, once more deeply moved, came to the tomb.

John 11:38

Yesterday, the latest in a wave of vehicle-based terror attacks played out on a bike path in Manhattan. 8 persons were mowed down during their Tuesday afternoon commute. It was the second major urban massacre in as many months.

The events that occurred in Manhattan this week and in Las Vegas last month awaken us to a lot of things. They snap us to the reality of dark evil around us. They force us to think about safety, civic responsibility, and compassion.

They also make us think about dying.

It’s more than a little bit ironic that Christians – People of the Cross, itself a symbol of death – talk so little about dying.

Death is mysterious, and we cannot make something mysterious simple. But we need to approach it, reflect on it. We need to prepare and possess a theology of death, something to help us think faithfully about what it means to live lives that will all eventually end.

I’d like to suggest three important concepts toward that purpose. The first is this: Christians must understand that death is inevitable.

Now, some of you are thinking: Wow, I never realized that! This blogger is a genius! That is probably the least profound, most obvious thing that I have ever heard! But hang with me for a minute. I think that we can be a bit more sophisticated than that.

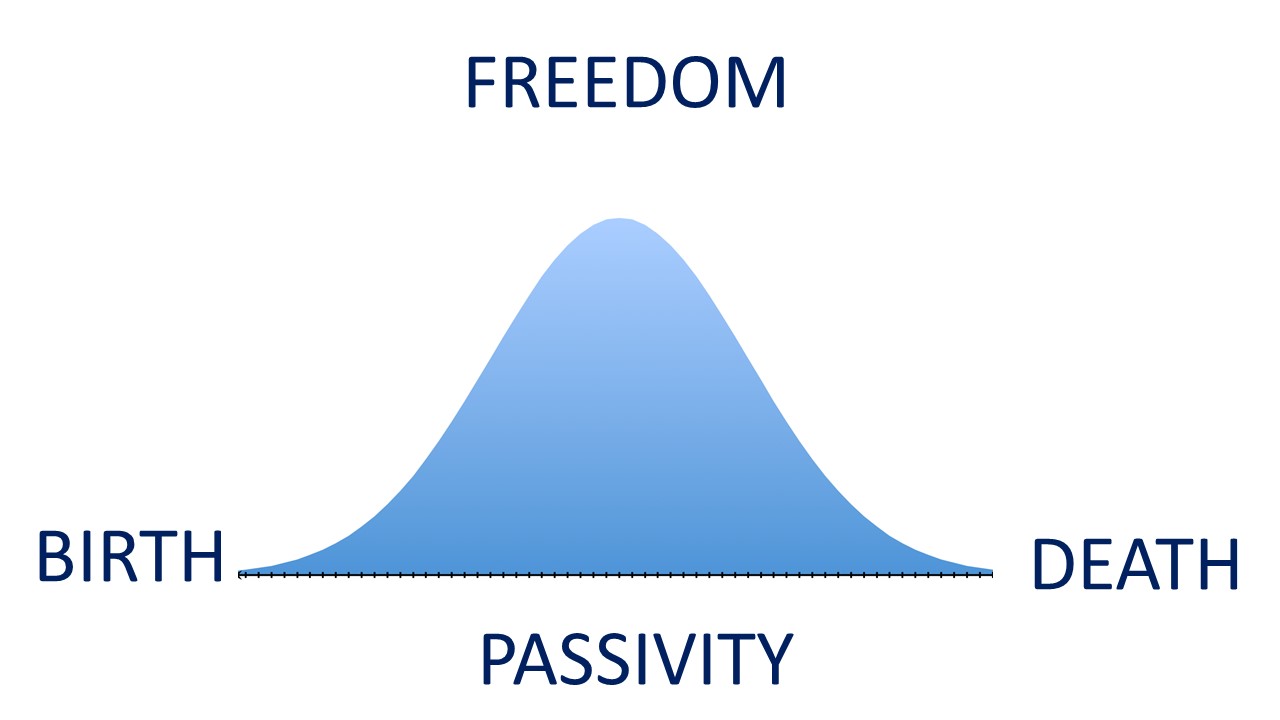

Karl Rahner was a Catholic priest and thinker from the 20th century. He believed a lot of things that I don’t. But on the matter of life and death, he wrote something that I find very compelling. He describes life as, among other things, a dialectic between freedom and passivity.

Rahner sees natural life something like this bell curve:

What Rahner is saying is this: there are times in life when you have the opportunity to make meaningful choices. There are some changes that you can bring about. But there are other moments and seasons in life when you have much less capacity to do what you want.

In your mid-life, you possess a fairly high degree of freedom. Your health is good, you have money, you have permissions. You have rights and opportunities to experience lots of different things.

It’s different earlier in life. You have more restrictions. You don’t have your driver’s license. You have a curfew. Then, as you approach the end of life, your body breaks down. People have to cut your meat for you. You become more passive.

Rahner and others point out that there are two points in life in which you have exactly zero freedom. You have no choice or freedom in being born – you weren’t in any way consulted on this – and you have no freedom to choose whether or not you die. As Hebrews 9:27 reminds us (should we require the reminder), it’s appointed once for all to die.

The second concept that Christian theology teaches is that death is tragic.

Dying is awful. It is wrong. It’s not “natural” in the theological sense. We believe that God created us to last and flourish, not to decay in caskets. And we believe that when we see death in any form, we should be upset.

Here’s where living in the formaldehyded modern West has changed us. When it comes to death, we are far more stoic and far more tranquil than most people historically have been. Death used to be public and civic and loud. It gripped and gathered communities.

Today we pay funeral directors to handle the messy stuff. We wear suits and ties. We try to keep our composure with an artificial piety.

I think that more than it does today (especially when it claims people outside of our immediate social orbit), death should rattle and disturb us. Jesus said blessed are those who mourn. Paul said that one of the jobs of Christian communities is to mourn when other people mourn. Sometimes the right response is authentic grief and lament. And sometimes – as when senseless violence is the cause of death – the right response is anger.

Do you know why it’s okay to be mad at death? Because Jesus was mad at death.

Remember the story of Jesus and Lazarus? It’s famous for being the text in which we find the shortest verse of the Bible. John 11:35: Jesus wept. And so we picture that scene as Jesus with a box of Kleenex and a bowl of pastel mints, just politely dabbing his eyes.

We’re missing something. Because you know what that story also says? Three verses later, it says that that Jesus walked toward the tomb of Lazarus with fire in his eyes.

What our English Bibles say is that Jesus was “deeply moved,” but what the New Testament author wrote was that Jesus was embrimaomai – a word which means “snorting” or “roaring” with indignation. Jesus was fierce like a bear or a lion whose cubs are threatened.

Jesus’ friend was laid low by some foreign pathogen – by some bomb planted by his enemy in Jesus’ beautifully-created world. And you know what I think Jesus felt? He felt the same way that the mother or the spouse or the child of someone who dies a violent and unnecessary death feels toward the killer. Satan, how dare you do this!

With his fist hammering on the rock tomb, he roared with fury at the fact that death lays low his children. Have you pictured Jesus this way? He’s emotional.

If we are not moved to love by death, if violence does not grieve us, if we are not indignant at murder, we aren’t thinking like Jesus thought.

Jesus seethed like a father who pounds the kitchen table after he receives a tragic phone call. Jesus is the mother, shaking the shoulders of the surgeon after he tells her that there was no way to save her child. Jesus is the friend, the lover, the Las Vegas police officer surveying the crime scene. Jesus wept. And Jesus burned.

You know what has always perplexed me about that story, though? It’s the narrative that precedes Jesus’ tears and his indignation about death.

If you look up a few verses from John’s description of the raising of Lazarus, you’ll see that prior to Lazarus’ death, a servant was dispatched to come and get Jesus so that Jesus could heal Lazarus. But when word comes to Jesus, John writes, this happened: Now Jesus loved Lazarus, so he stayed where he was for two days (John 11:6).

For a long time, this made no sense to me. If death made Jesus so angry, why did he stay put? Why didn’t he prevent Lazarus from dying? And for that matter, If Jesus is so upended, by death, why didn’t he cause the New York terrorist’s truck to stall out? And why does he allow the miscarried child to die? And why doesn’t he protect the murder victim by striking her attacker with malaria before he could attack?

I honestly wish I had the complete answers to those kinds of questions. Death always drives us back, in some sense, to the Problem of Evil.

But I think I can understand part of the answer. Part of the answer is there in the story of Lazarus. Look carefully: While Jesus loses his cool, he never loses control. Yes, Jesus is emotional, but he is never impotent. Though he is roaring, he remains the Resurrection and the Life.

That’s the final, audacious claim of our theology – That death is not final. In the end, Jesus sabotages Satan’s sabotage. And that when we die, the worst thing that the enemy can do to us becomes the greatest thing that could ever happen to us. The end is the beginning.

Zachary Hayes says this: It is the Christian faith that what appears as a possible threat of nothingness is in fact the condition for the realization of the fullness of life in a dimension that transcends our historical experience.

How is that possible? It’s possible because Jesus gets one more chance to roar.

In the last book of the Bible there is an amazing passage about Jesus’ heavenly glory. When the narrator of the story, John the Seer, beholds Jesus, what he sees is a Lamb looking as if he had been slain.

But you know what happens right before John witnesses the Lamb? Right before the Lamb appears, John is told by a heavenly elder to look carefully. Don’t miss this: this is where the story becomes even more amazing. Revelation 5:18 says that the elder tugs on John’s robe and says – Behold, the Triumphant Lion!

John’s eyes took in the sight of a slain Lamb. He realized that painful wounds had been opened, that blood had been spilt. Death was real, and it had claimed the life of the Lamb.

But that Lamb, the elder declares, has a secret identity! The Lamb is really a Lion!

This was the Lion that roared at the tomb of Lazarus. And this is the great and final Lion that will someday roar again from Heaven’s throne. And that roar will shake and shatter and transform the world so that even death itself will look different.

Are you ready for that roar?

Rahner is right. Your freedom will come to an end. It might be a stroke, it could be an accident or violence or a heart attack. But your freedom will eventually come to a close. So today, will you use that freedom in the greatest and most important way you can?

Mourn for the lambs around you. And trust the power of the Lion.